“Write about what you know,” my journalism teacher, Mrs. Orsini admonished. What did she mean by that? It was rather like being told, “Work for a living!” At fourteen such exhortations were meaningless. I stared, both fascinated and repelled, at Mrs. Orsini’s long painted toenails. She was married to a podiatrist, she had told us girls. Why would anyone choose that field? What induced her to marry such a man?

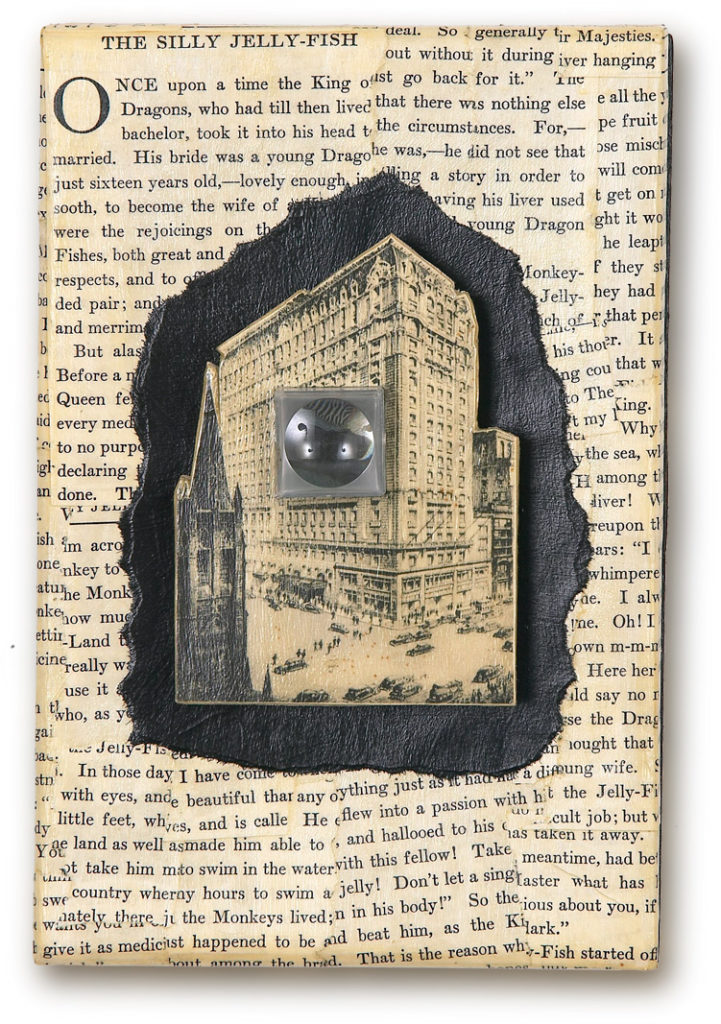

“Hotel I” by Brian Booker

Mrs. Orsini’s earnest horse face, her long sandy hair held back by a clip, the exotic glamour of those painted nails, all made me want to be the best writer the world — or at least Montclair, New Jersey’s “College High” — had ever seen. “Everything is material,” I told myself. I yearned for art and beauty. I wanted to be disembodied, ethereal as a Rosetti or Burne-Jones. At fourteen I shrank even from the word “flesh.” It reminded me of earlobes, it reminded me of rare steak. Flesh — all flesh is as the grass. It set my teeth on edge. I had not yet gotten my period. During study hall I ran to the school library and read avidly about freaks. I was convinced I was one.

Weird anatomical books, with detailed drawings of freaks. I stared at them earnestly, as if trying to read their secrets. Did they mind? Did they feel bad? I spent endless hours in the bathroom. “You’re beautiful,” I told myself into the mirror. I cupped my face first this way, then that. I was a marquis, with powdered wig, adoring my beautiful young self. “Those innocent lips,” I muttered.

“Mother,” my sister Cecily banged on the bathroom door, “Kathleen won’t let us in. She’s been in there for hours.”

“Kathleen, come out,” my mother would call feebly from downstairs. I could tell she was deep in a book.

“Mother, mother!” Cecily yelled, pounding.

“Later, my beauty, later,” I promised my reflection in the voice of the marquis. I kissed my fingertips to my image, opening the bathroom door with dignity. Not speaking, I stalked past Cecily and slammed the door to my bedroom.

“What’s for dinner,” I demanded of my mother.

“Hamburgers,” was her reply. That did it. Better to sit upstairs alone than to suffer the half chewed meals in my younger sister’s and brother’s open mouths. The thought of food — and wasn’t hamburger “flesh?” — disgusted me. I couldn’t stand meal times with the family. Instead I sat locked in my room, reading the Lives of the Saints. How I longed to be one! But the eating habits of the Peter F. Drucker family were as nothing compared to the bizarre food behavior of lady saints. I closed the book.

Later I deigned to go downstairs. “What happened to all the cookies I baked yesterday?” my mother asked, counting them. I stared her down, unblinking. It was a test — if she dropped her eyes first it meant I really hadn’t eaten a dozen cookies this afternoon. I was bold; I was brazen; and my mother looked down first. I was a liar, a miserable sinner. Perhaps I should convert to Catholicism. Like Victor Hugo, I needed someone to confess to. But my sins seemed to multiply faster than the confessions. I become my lazy half-German half-Jewish self again, locked in my room and reading Thomas Mann.

The eating habits of the Peter F. Drucker family were as nothing compared to the bizarre food behavior of lady saints.

I was on a starvation diet. I would be thin, thin and poetic. I would pray a lot to — something — even though I despised religion, the “opiate of the masses.” I would look like the floating lady saints or the lady with the unicorn in a long dress and pointed hat in the books my father gave me. No matter that I was not blonde.

“Kathleen, have you finished your homework?” my mother called upstairs into my room. When would she ever leave me alone? Couldn’t she see that already I was a great artist, alienated, standing outside, always watching the blonde blue-eyed ones, just like Tonio Kröger. I hugged my small dark hating brooding alienation.

“Nyah nyah, she hasn’t done it yet,” my brother tattled. Cecily shrieked with glee, pointing her finger and hopping up and down.

What betrayal! Hadn’t I, just the night before, in my fantasies that always resulted in sleep, managed to save that same Cecily from the clutches of a Mad Rapist? Hadn’t I run with her through fields and forests until, my clothing ripped by twigs, and my lovely body torn and scratched by thorns, I fell, a lifeless bundle clutching my dear baby sister, right at the beautiful painted feet of Mrs. Orsini? “She was special,” Mrs. Orsini later told my family at the funeral. “If only we’d appreciated her more,” sobbed my ever-critical mother.

Another time I single-handedly saved my family (and the rest of New Jersey too) from destruction, when, after a magnificent swordfight on deck, the pirate ship tossing and heaving, I fell clutching my side, flinging away the grenade. I barely managed to crawl to the feet of my modern dance teacher (sandaled) before I expired. The ship’s doctor had to cut off my clothes, so tightly were my budding breasts bound. “Why, she’s a girl,” the whole pirate ship exclaimed. “A mere girl and she saved us all.” At this point I would fall asleep, shedding a few delicious tears.

“Don’t chew with your mouth open,” my mother scolded my brother Vincent. He closed his mouth, then opened it horribly in my direction. Vincent was my best friend but he was betraying me.

“I hate you!” I stood up and screamed, picking up the ketchup bottle like a baseball bat and swinging it at him in wide arcs. Streams of ketchup wreathed the beautiful new wallpaper — just put up — by our mother — in the dining room. I was sent to bed without eating.

A neighbor had brought over a lovely cake, and it sat on the kitchen counter, piled with frosting and rosettes and pink flowers. Standing in the cold kitchen in the middle of the night, feeling sorry for myself, I scooped up one fingerful of frosting, licked it, and smoothed out the little dent in the cake. No one could possibly notice. I took another dab. And another. The next morning my mother discovered the bare denuded sponge cake, its crumbly surface exposed. What had happened? “I don’t know,” I said, protesting my outraged innocence. “Maybe it was always like this. Maybe a burglar came in.”

For the next months I sat at the dining room table pulling my hair down over my face and chewing the ends. They were salty. I’d show them. I was an idiot out of David and Lisa. I was a schizophrenic. Someone was promising me a Rose Garden, taking me into an expansive Viennese lap. I would go completely bats. I would never have to do the dishes again. “Gubba gubba,” I murmured, trying to go even more crazy, if that was possible.

“Kathleen, take that hair out of your face,” my mother said impatiently. “Are you going to look like that when a Boy takes you out?” My brother and sisters, complaint hyenas, laughed. I removed my hair with dignity. Don’t worry, mother dear, no such possibilities need ever occur.

“Write what you know.” I was a princess, I was a changeling. I knew only the world of princesses, silks and satins, courtiers and fawning servants. The Druckers were only my adopted family after all. Didn’t they realize how lucky they were to have a princess in their midst? They’d be sorry they’d treated me so badly, when they found out. “I didn’t know. I really didn’t know!” My mother screamed for mercy just before she was beheaded.

I held out my open palm for pardon. “Stay the executioner’s hand,” I commanded.

My mother fell to my feet in gratitude. “My daughter, my darling daughter,” she sobbed. “I owe my life to you.” Salty tears fell into my hair as I lay on the pillow. I sucked the ends happily.

I had already trained the family in euphemism, tact and courtesy. There were names for unmentionable things. “Harpsichord,” for instance, was our family name for the toilet. Once, when Time magazine came to interview my father, the reporter wrote, “Drucker’s children are so disciplined that they even excuse themselves from the dinner table to go upstairs to practice.” Time printed that. “I have to go to the Harpsy,” we would yell, running away from the endless dishes.

“The family was so repressed,” I later complained to our mother in a post-adolescent post-mortem on “Our Problems.” My mother and father looked baffled.

“But Kathleen,” my father gently reminded, “after all it was you who insisted on the “Harpsichord.”

Ah. “It sounded better,” I said. Tinkle, tinkle.

“Write out of your experiences,” my teachers said.

“Come out of the bathroom,” Cecily shrieked. I looked at the toilet paper (still a freak), and then bid goodbye once again to my lovely reflection. I was working on a term paper and trying to avoid it. “Costumes through the Ages” was the theme I had chosen; a hundred page term paper would be a snap. Codpieces fascinated me; the things men wore on their fronts to hide their real fronts. I thought it would be fun to draw all those costumes, forgetting I did not know how to draw. Soon mutton sleeves, bustles, and even codpieces disgusted me. My father, “Fa,” my real father, not the “Peter Drucker” belonging to everyone else, encouraged me on.

“Come into my study,” he said, ever patient. He was busy answering letters, not really paying attention. But he did manage to dig up some tracing paper, and together we copied pictures of costumes out of the encyclopedia. We spent hours that spring sprawled on his scratchy carpet, while we carefully colored in puffed sleeves and doublets and tights and codpieces within in the penciled lines. “Only thirty more pages,” he encouraged, picking up another crayon.

The next year I chose the “Common Diseases of Mankind.” I wanted to impress my biology teacher, a large woman with a thick-coiled braid, who despised her female students. I found the Merck Manual and copied it cover to cover. “In your own words, Kathleen,” my father exhorted. I was pale, I felt sick. I fainted through every disease, from anemia to xenophobia. “Here,” said my father, “you read to me, and I’ll type it.”

“Ugh. Gross!”

“A disgusting project,” my father agreed, laughing. I lay on the scratchy carpet, a wet towel over my eyes. He sat at his old typewriter, pecking away. I tried to paraphrase but tedium overcame me.

“I can’t, I can’t,” I moaned, as we got through the L’s (leprosy) and the M’s (malaria). The letter P as in (plague, black) was coming up. My father giggled that surprising high whinnying laugh of his that had somehow morphed through my sister Cecily.

“Never mind,” he said kindly, looking down at me from his typewriter. “Just a few more weeks. Only sixty five pages more to go.”

Not only was I a freak, but my family was as well. We were intellectuals; we didn’t have television. Mr. Rogers never visited my neighborhood. We were expected to participate in “intelligent conversation.” But since there were four children, conversation never got much beyond “He hit me,” and “She hit me first.” I hated the savages. Only my brother learned, by dint of much persuasion, to bow when I entered the room. He was a lower element, of course; but my sisters were hopeless. Uneducable. I was living with apes. A wild child.

I wrote plays, composed operas and musicals. The casting director as well as the star, I pressed my brother, sisters, and all friends into service. After my father’s funeral, when the family gathered for remembrances, my brother and sisters remembered the summer during which we endlessly enacted the fascinating theatre piece “Coronation.” I of course was Lilibet; my beautiful sister Cecily, she of the golden curls, played Margaret. My brother Vincent was the Archbishop of Canterbury, patiently crowning me again and again. But my adorable youngest sister Joan remembered being forced to stand at attention holding a butter knife, not even a sword, she was too young for anything that might really cut. She was our Good Sport, our “Page.” All summer long.

My mother made me a puppet theatre, and beautiful handmade puppets with costumes from scraps of lace so that I could write out my fantasies and enact them on our hall stairs. My two best friends were Aurora and Gabriella Arciniegas, whose father was in exile from his post in Columbia, We scribbled torrid novels, pages and pages every week, reading them on the phone to each other whenever our parents would let us. We met at their house every weekend, read the sappy things aloud and wept for the romance of it all. Mrs. Arciniegas would then play the mandolin for us: she played in a Mandolin Orchestra; and Mr. Arciniegas came in and joined us for a South American lunch in which Guava Jelly seemed to be the most fascinating ingredient.

My mother raced up mountains in Colorado during summer vacations and walked around our neighborhood on stilts…

At that time my mother, who sometimes seemed to encourage my fantasies, Ruined My Life almost every weekday afternoon by making me baby sit for my baby sister. When no one was looking I kissed little Joanie over and over. But in public, it was just an accident I happened to be behind the handles of a baby carriage. Proust never changed diapers.

One day the telephone tolled. It actually tolled for me! “Kathleen!” my mother shouted upstairs. “A Boy’s on the phone!” My sister and brother hastened to listen in on the extension.

The Boy, thick and pasty, came to the house to pick me up. Everyone looked him over. “It’s so disgusting the way he tries to kiss me,” I complained to my brother. He was sitting on my bed, late at night, and for once I didn’t tell him to move his hairy legs and feet. “All that spit!” My brother laughed, sharing that shiver of horror. That summer my parents ruined My Life again, by insisting the Boy have me home before eleven.

My father and I went to look at colleges and on the train back from a visit to Swarthmore I read Gone with the Wind. “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn,” I whispered to myself at night, waiting for Rhett Butler to come and take me. I was beautiful and brave. And I was leaving home. Emotions were running high.

That year “the parents” changed the rules on our weekly family Scrabble game. Exams were looming and expectations were high. We played Scrabble — in Latin — each week. How could you understand English if you didn’t know Latin? My father of course always won. “Hah!” he would exclaim, in satisfied triumph, the huge Latin dictionary lying on the floor next to the Scrabble board.

The first child in the Drucker family to go to an American college, I was filled with anticipation and dread. It was an event: the whole family would drive me to Oberlin college.

“Stand still,” said my mother, pinning a new dress onto my busty frame for the high school graduation party. The dress was chintz with pink and green cabbage roses. “Do you want to slump like that on your wedding day?”

“Let her talk,” I thought, slumping further. “You can’t go home again.” I’d never get married and end up like Her. My mother tried unflaggingly to get me to stand up straight. But to my dismay I had gone from no breasts to a quite decent bosom, which I wanted to hide.

“I’ll pay you fifty dollars if you have good posture,” my mother bribed. I was a tough cop, uncompromising, the kind that doesn’t take bribes. “Fünfzig,” my mother hissed at me across the dinner table in German. This was to be our “code word.” It meant “fifty,” as in “fifty dollars.” But being in German, that spoken exhortation was for her and my ears alone. I pretended not to hear or understand. “Fünfzig!” I lowering my chin to the table and looked up, mournfully lolling my eyes: “you see what I have to endure?” No one would ever understand me.

“The family,” but especially the “folks,” later to be the subject of our endless discussions, were too weird to be believed. “Why aren’t you like the other mothers?” I exclaimed in exasperation to my long-suffering mother. She was raising four children, cooking our favorite meals, knitting our socks and sweaters and mittens, sewing our clothes by hand, taking care of us and our father, reading everything he wrote, and getting her graduate degree in physics long before it was fashionable for women to do so. She was funny and full of life. She had carpentry projects, built wheelbarrows and sleds for us and furniture. She raced up mountains in Colorado during our summer vacations or walked around our neighborhood on stilts, showing us how she could throw one stilt over her shoulder and hop. On April Fool’s days she sewed up the bottoms of our father’s pajamas, and short-sheeted our beds. My father always acted surprised every time.

“Hah!” he shouted, every year. “What’s going on?” He looked absolutely delighted.

“April Fool!” she cried enthusiastically.

But it was Doris Drucker’s going to Graduate School in the fifties that made her different from other mothers. “I’ll be a Juvenile Delinquent. And it will be all Your Fault for neglecting us!” I muttered darkly when she was “too busy.”

I looked round the family dinner table. With only a little effort I could block them all out. I was Ur, a beauty from another planet. Sent among the humanoids I did not comprehend their vulgar chatter. “Fünfzig.” I tried to both slump further and ignore them all. I was a slender being composed of light, beautiful and still. What was that strange language they were all speaking?

At night we could hear our parents companionably chatting and laughing from the door of their bedroom. “Come in, Kathleen.” my mother called. The “sibs” were long in bed, and I got to stay up a whole hour later than them, dreaming away time when I might actually have been learning something. I went in and flopped on the parents’ bed and picked through their reading matter: Womans’ Day and books of knitting instructions and physics texts and Scientific American lay on her side of the bed; history and politics and economics texts and the collected works of Anthony Trollope on his.

My father gave me books for Christmas, his favorites: Vanity Fair, Huckleberry Finn, and histories of the Middle Ages, Eleanor of Aquitaine, and all of Dickens. “It is a far far better thing…” Was my mother Madame De Farge? I prepared a soulful face with which to approach the gallows. I would be noble to the end…

“Have a chocolate,” my mother said, as she lay in bed reading. “And bring me one too.” My father didn’t look up from his book but my mother moved over to make room for me. The chocolates were hidden in her underwear drawer, buried under silken slithery things. I got them out, brought them into the bed. They had creamy centers; mushy. I lay down next to her, my nose in a book just like my father.

“There, there,” he said abstractedly. Just the sound of his voice was soothing to me.

“Tell me about when you were growing up,” I murmured as we all read together.

“She’s my best student,” Mrs. Orsini told my parents at my High School graduation. They looked surprised. In four years I hadn’t written one word of truth. Where life was blood and noise and food and bathrooms and endless scrapping I wrote about costumes and flowers and beauty and lofty thoughts. Perhaps Mrs. Orsini lied to everyone’s parents. “Write what you know.” Nothing I knew seemed important.

For writing, real writing, is ultimately betrayal. In my journal at night I scribbled furiously, almost unconsciously. Years later, when my mother gave me the box of things of mine she had saved from our sold childhood home, I fell on my old journals with hope and discovery. I wanted to find out who I had really been, what I had thought and written about. “They don’t understand me.” “I’m mad at her/him/them,” were the endless variations upon a theme, written in furious handwriting, so vehement at times it punctured the page. Occasionally I felt a bit guilty. Did anyone want to read these writings of a young author — if this was truth, please give me Beauty anytime.

My other “true” writings were plays, for which I bribed “the sibs” to perform, operas for myself and friends, and stories — my mother’s favorite opened with the line, “Dead cows tell no tales.” Always it was a “dark and stormy night.” I was neglected, unloved, unappreciated, almost an orphan.

While real life went on around me, the household swirling with feelings and action, I dreamed my way through books and heroism. “The offended sausage,” my mother called me, in some translation of a German proverb. I was almost a swan, I thought — couldn’t my commoner mother see that? I was aloof.

“Kathleen is the last of the Victorians,” my father proclaimed. Peter Drucker was given to oracular pronouncements: His daughter, The End of Economic Man. I tolerated him with respectful impatience. But for some reason this particular pronouncement irked me.

I looked at my mother but she was looking down at a book, knitting as she read. She was busy figuring out the Snowflake Pattern and the Quantum Theory with two different parts of her brain. Upstairs I could hear my brother and sisters squabbling. “They’re still in the ‘vulgar stage,’” I thought pityingly. There was also a certain delight, thinking of them frozen and vulgar forever, while I went on to college and became a great intellectual. I already planned to study art and philosophy and classics. Nothing too full of life. “Yes, the Last of the Victorians,” my father proclaimed again with satisfaction. He was maddening!

My mother looked up, abstracted. “Kathleen, would you like to play some chess?” she asked mildly. “And perhaps you’d like a chocolate. You know where they are.” I started setting up the pieces on the board. I was still not able to beat my mother at chess, but for once I didn’t even mind that she won. My father buried his nose in a book on English History. I had already read through his whole library, looking for the racy parts.

Little did my parents, poor souls, suspect that in just two short months I would be starting to become Simone De Beauvoir. Small, dark, sophisticated. Their daughter, having deep discussions with Sartre. In a dress my mother was even now cutting out from chintz material left over from our porch slipcovers. In the skirt and weskit she was sewing out of fake fur leopard skin. In the wide gore poodle skirt with mother-embroidered white poodles jumping round the hem. I would hack off my waist-length hair with nail scissors to resemble Joan of Arc, or perhaps Jean Seberg, racing hand in hand down those cobbled Paris streets. I would take a pen name, yes, a nom de plume and live on absinthe.

“Je suis comme je suis,” I would be humming knowingly. For I already intended to write about, if not to know, Free Love. I would know — everything, in fact. And write about it too! The minute I left New Jersey.