Back in the 1940s my family moved into a brand-new house in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn, New York, neither then nor now one of Brooklyn’s chic neighborhoods. It was a two-story attached brick row house identical to its neighbors. Modest, middle-class, affordable, a compact congenial house with a small front and back porch, front steps bordered by a tiny strip of grass, a driveway with a wall that would prove useful for handball. I remember moving day quite well. The house had casement windows in the living room that opened on to the front porch, and our piano, dear to my mother and later to me, was maneuvered in through those obliging casement windows. My father was proud that he could make the move and announced to everyone he knew that he was living in a Trump home.

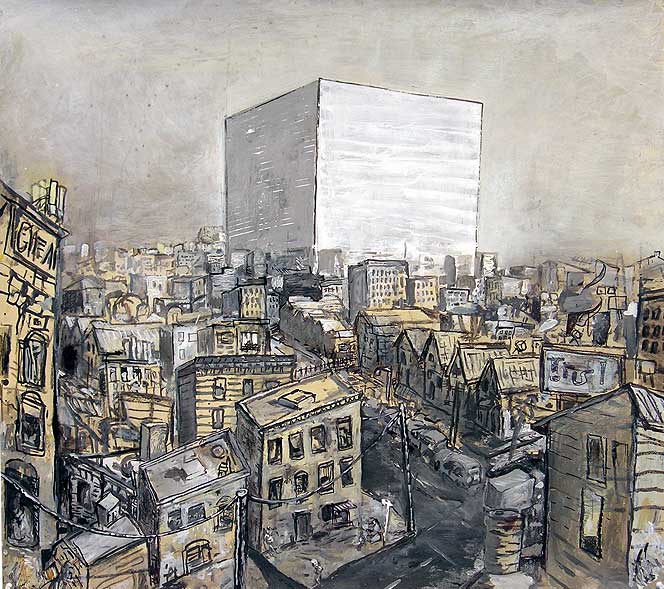

New Building by Dale Williams

Three small girls around my age — today they wouldn’t be allowed out without a parent — stood on the sidewalk watching the piano caper and immediately offered to be my friends. That and the casement windows in every room and the three chimes in the living room that trembled when someone rang the doorbell endeared the house to me. I grew up there and whenever my father made his announcement about living in a Trump home I imagined Mr. Trump as a bountiful kindly gentleman, rather like Mr. Carmichael in A Little Princess, one of my favorite childhood books, who supplied deserving families with nice places to live.

Only recently with the candidacy of Fred Trump’s son Donald that has arrived like a plague of locusts — except that locusts are expected periodically and Donald was not — did I start to wonder who exactly this Fred Trump, our longtime landlord, was? What did Donald come from?

Fred Trump, the son of German immigrant parents, started out in real estate at the age of 15. Too young to sign checks, he needed his mother to do it for him. He became one of the largest developers in Brooklyn, comparable in scale to the better-known Sam LeFrak in the borough of Queens. Donald liked this arrangement: “This way, I got Manhattan all to myself!”

During and after World War II Fred Trump claimed to be of Swedish descent; as one of his associates put it, many of his tenants were Jewish and it wasn’t a good idea just then to be German. Trump pere died in 1999 at the age of 93 with an alleged fortune of $250 to $300 million. His lengthy New York Times obituary called him “one of the last of New York City’s major postwar builders” and also remarked on his “silent-movie star” looks (not inherited by his son). In addition to Flatbush, he owned houses and apartments all over Brooklyn: Coney Island, Bensonhurst, Sheepshead Bay, Brighton Beach, as well as some in Queens, many of them intended for returning veterans. In 1954 (while I was still living in the house!) Trump was investigated by a Senate committee for “windfall profits” made by acquiring ill-gotten loans from the FHA.

This news was dismaying; it destroyed my fantasy of the small-time benevolent builder, and my family as the lucky recipient of his largesse. (Asking around now, I find that many people knew the scope of Trump’s empire, while I had kept my childhood illusions.) Plus I didn’t relish feeling any connection, however remote, to Donald Trump.

During and after World War II Fred Trump claimed to be of Swedish descent…

In 1973 the Justice Department Civil Rights Division sued Trump for discriminatory rental practices; his employees were instructed not to rent to black families and to keep applications coded by race. These practices were unearthed by the Urban League’s fair housing program, which sent white testers to apartments denied to black applicants. When the white tester was offered the apartment, the agent was caught red-handed, as it were.

This fact alone wouldn’t have surprised me given the rental policies of those times. What was surprising was yet another degree of proximity. For in the late 1960s I worked at that very fair housing program, run by the indomitable Betty Hoeber, who nearly single-handedly forced landlords large and small to obey the laws, and cleared the way to a more integrated city. I worked as a checker, I advised black families on where to look for housing, I followed cases we brought to New York’s City Commission on Human Rights. Had I not left to return to graduate school in 1970, I might very well have gotten involved in the case against Fred Trump, which resulted in his being forced to advertise apartments in minority newspapers and to list them with the Urban League.

All of this cast a cloud over the memory of the unprepossessing but comfortable house I grew up in. Nowadays I feel a bit of a shudder when I recollect my father’s assertive voice boasting that he lived in a Trump home. We enriched the Trump family fortune for nineteen years.

One Comment

Error thrown

Call to undefined function ereg()